Field Gear: Optimizing Cephalic Protection

Ohio’s climate, and the unique path of human evolution, mean that naturalists need clothing, including head gear. Field work is most effective and satisfactory when the odonatist is safe and comfortable. However, pragmatic considerations are often influenced by psychological and social considerations. This short ‘how to’ piece provides a decision model for the intimidating process of choosing the right outdoor hat.

Today’s economy presents the field worker with a bewildering variety of headpiece options, a condition that can lead to a counterproductive condition called ‘choice overload’ or ‘overchoice’. Fortunately, the negative relationship between choice assortment and sartorial satisfaction is reduced as people gain familiarity with the domain. A measurable relationship exists between the reduction in cognitive paralysis, and the attainment of relevant expertise. Although not as thoroughly explored, it seems likely that the actual validity of this expertise is not as important as the belief in it. Towards that end, we offer an 11-dimension model encompassing the major physical and anthropological functions of a field hat. Arranged in rough order from least to most expensive, 6 basic models can be considered as representative of the vast majority of hat styles commonly worn in the field (additional types could be added, such as the bowler, the fascinator, and the yarmulka).

For very practical reasons, many cultures have developed headgear with a full brim, covering all sides of the head, providing shade, protection from precipitation, and especially important in our context, reduced solar glare. This latter feature facilitates the observation of small insects, especially when looking at them through the viewfinder of a camera or binoculars. The ubiquity of visors on caps (flat hats designed for maximum mobility) highlights the goal of reducing highlights. Although they vary in their ability to shade the ears and neck, all outdoor headgear in our context provide at least some glare reduction for the upper half of the face. This emphasis on anterior shade drives one of the many tradeoffs confronting design choice, the compatibility with holding a large camera in vertical orientation. The large and stiff brim of the traditional cowboy hat make it virtually impossible to exercise verticality. Although it is located at the opposite end of the affordability scale, it has this consideration in common with the baseball cap. Although it may be socially unacceptable in some contexts, the baseball cap can be rotated 180 degrees, thereby avoiding portrait conflict. The remaining 4 categories of hat benefit from modern materials, providing 365 degree brims offering full shade and weather protection, while being flexible enough to accommodate alternate orientations.

The fortuitous preference of odonata for nice weather somewhat reduces the significance of wind resistance (‘cephalic stickiness’), but the proximity to not just water, but often yucky smelly water, increases the relative benefit of a hat that stays on the head in spite of a stiff wind. The greatest degree of wind resistance is afforded through they use of a chin strap, which unfortunately creates another choice tradeoff which can contribute to cognitive overload: with the exception of a few movie stars (and Australians), most people look dorky with their hats strapped to the lower half of their face. The most effective approach to this problem is the knotted ‘Tuckaway Wind Cord’ featured on Tilley’s brimmed hats. Surreptitiously resting within the crown as the default mode, it can be strapped around the dorsal section of the cranial cavity (‘occipital mode’) during moderate winds, a position with minimal aesthetic impact. Most people reach a threshold at approximately 27 knots of wind speed, at which point practicality outweighs appearance, and the wind cord can be used as a standard chin strap.

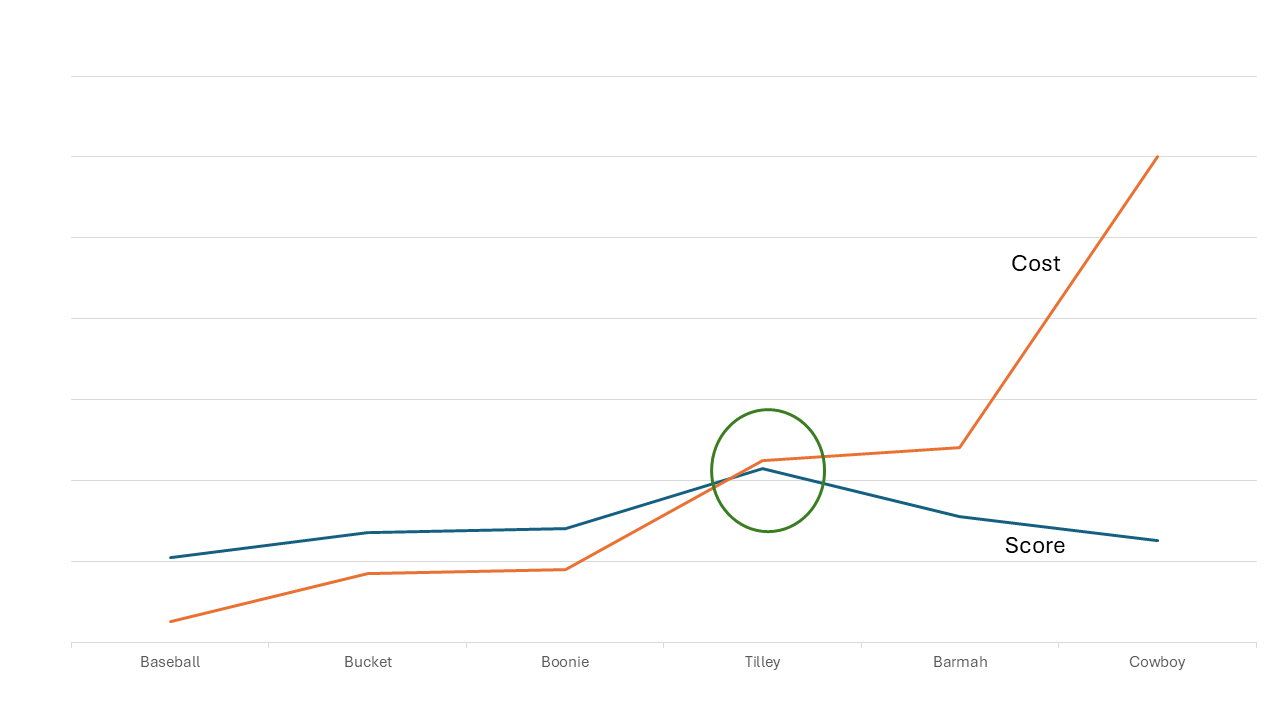

The 11-domain model suggests that the Tilley Airflow, may indeed be the optimal form of field head gear. As shown in the cost/utility graph below, leather and felt hats are more expensive than cotton and polyester ones, while providing relatively less utility in the field, especially if the field is a marsh. Certainly individual preferences and other circumstances vary, and in those cases, this same model should still be useful with a different weighting applied. An Akubra or Stetson is a stylish and practical item of clothing when walking around the park on a cool Fall day. But if you wear a nice cowboy hat into the summer swamp, your head will sweat, and it’ll interfere with your camera. If it blows off, it’ll sink like a rock, and if you do manage to retrieve it, you’ll never get it clean. A Tilley is not only cooler in the heat, but it provides several additional levels of resiliency. The wind cord make it less likely to blow off, but if it does, the hat floats, and it can be washed. More research needs to be done on the washability of ball caps, but for field workers who are OK with the clumsy visor-style brim, their low cost may make them the best personal option. If compatibility with auto headrests is added to the model, it significantly increases the relative standing for ball caps.

When engaged in field work, wear clothing that not only protects you from biting insects and sun, but also provides a plausible visual identification for suspicious locals who may legitimately wonder what the hell you are up to. Just as hunters and fishers control their external identity narrative through the accoutrements of their avocation (ie. guns & rods), dragonfly researchers look less threatening and more credible if their hat sends the message ‘I am a harmless nature enthusiast’. Many dragonfly enthusiasts struggle with the competing dual identities of nerdy naturalist and normal person. Naturalist identity formation (NIF) theories offer a conceptual framework for considering this dilemma. Early studies, and practical experience, suggest that not just external perception, but also self-identity, can be usefully manipulated by not wearing the field hat when around other people. The NIF theoretical model help us to entirely avoid consideration of otherwise suitable gear, such as the politically incorrect pith helmet, and it explains why the baseball cap communicates a different message than the military style patrol cap. Likewise, although the stiffer brim of the boonie hat offers protective and photographic advantages over the bucket hat, it its political associations represent an ambiguous narrative that may not be consistently received at natural history conferences.

In summary, clothes make the naturalist, although the opposite is true for the naturist. In all cases, hats provide superior protection.